|

IHS

ENGINEERING 360 16 FEBRUARY 2016

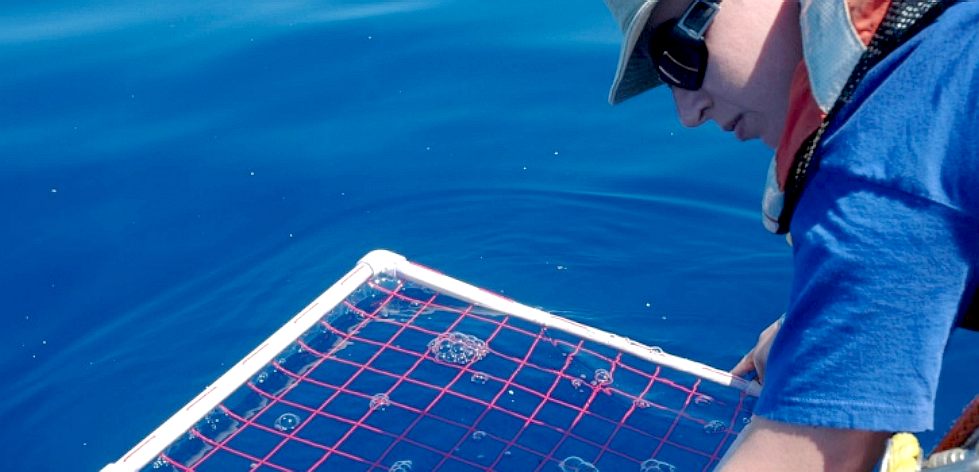

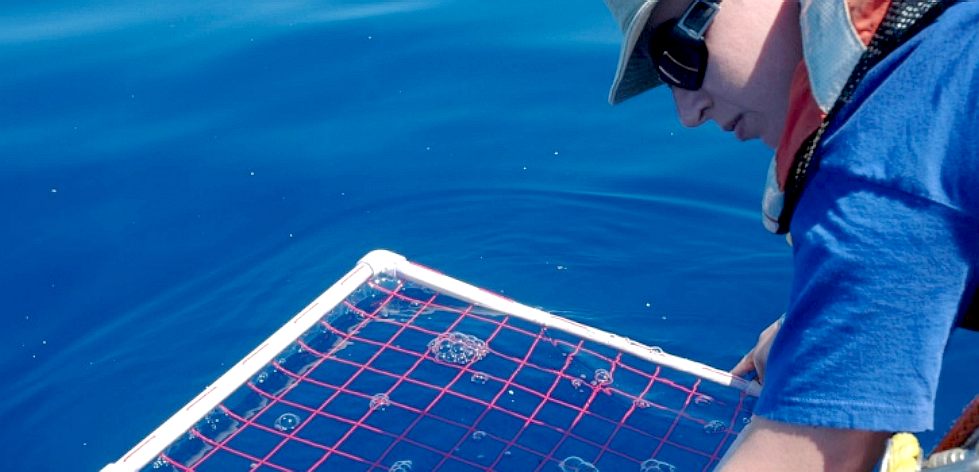

SEAPLEX

- Chief scientist Miriam Goldstein used a quadrat to study confetti-sized flecks of plastic debris in the North

Pacific Ocean Gyre.

If it wasn't for the work of these marine biologists, nobody

would know there was a problem for engineers to tackle.

CLEANUP

SYSTEM AIMS TO STEM THE TIDE OF PLASTIC POLLUTION

Although it’s difficult to calculate the total amount of debris in the ocean, oceanographers estimate that 8 million tons of plastic trash enters the water annually. That quantity likely will grow as demand for plastic-based consumer goods is expected to spike over the next decade, particularly in the Asia Pacific region already struggling with unmanaged plastic waste.

The

Ocean Conservancy

says that without immediate action, the seas could hold 1 pound of plastic for every 3 pounds of finfish by 2025. More plastic pollution equals more risk of entanglement and ingestion by marine animals. Many oceanographers and conservation organizations say that prevention is the fastest, most reliable method to stem the tide of plastics polluting the ocean’s ecosystem. However, several groups of scientists and engineers are exploring new ways to retrieve debris at sea. These large-scale debris removal projects use solid engineering principles yet leave marine debris experts questioning the impact on oceanic life, the disposal of the collected plastic trash and other unforeseen consequences.

THE

OCEAN CLEANUP PLAN - Is so crazy it just might work. The largest marine cleanup project in history is set to launch later this year (2016). The goal: Get rid of half the plastic garbage currently in the oceans. It’s bold, it’s ambitious, and it’s popular with the media (although less so with scientists). But will it work?

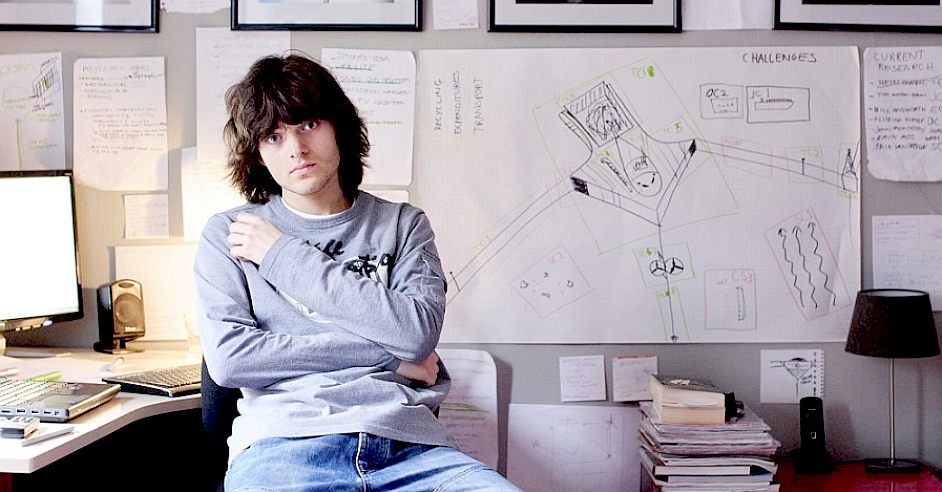

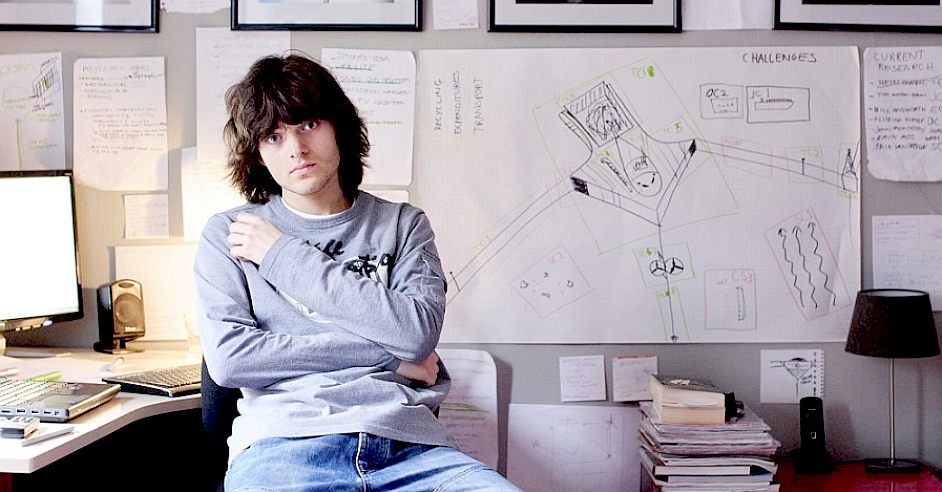

Dutch engineering student Boyan Slat shocked the environmental community when he announced in a 2012 TEDx talk that he had invented a way for the oceans to rid themselves of plastic with minimal human intervention.

After all, we’re funneling a jaw-dropping 8 million tons of the stuff into the oceans each year, in addition to the more than five trillion pieces of plastic garbage already swirling in the waters. Could a then-17-year-old really have found a simple solution to this massive problem?

Many environmentalists didn’t think so, but Slat’s idea was nonetheless intriguing. He proposed building a stationary array with floating barriers that would filter and collect floating plastic using the ocean’s natural currents.

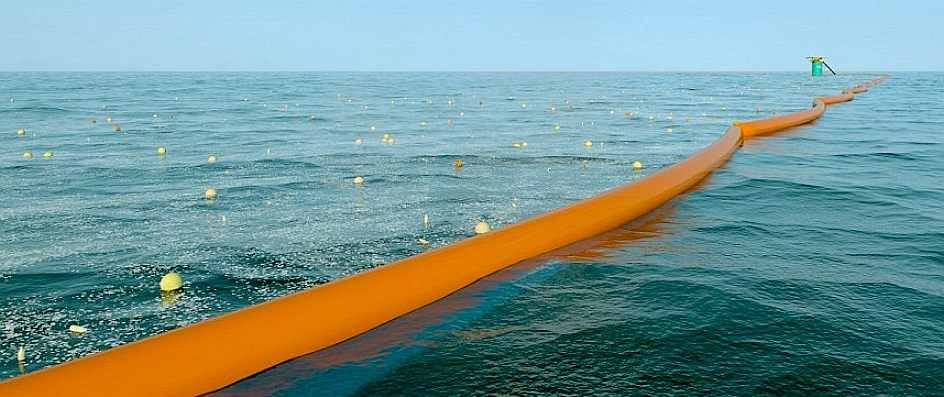

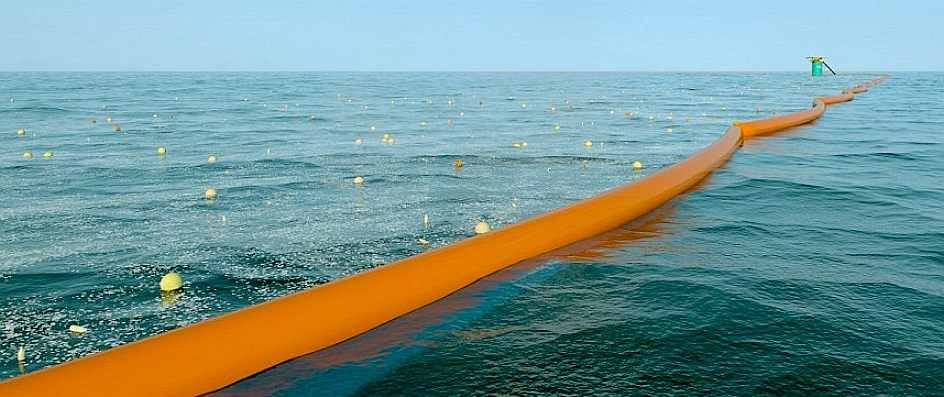

Unlike

wind farms that are relatively easy to spot on radar and have

large gaps in between units, a continuous boom that is low in

the water, could give sailors problems - especially of the single-handed

kind.

MOVING

CLEANUP TO THE HIGH SEAS

For decades, the most cost-effective and efficient method of debris removal has been shoreline cleanup in debris accumulation areas, says Nancy Wallace, program director for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

(NOAA’s) Marine Debris Program. On these beaches, trash is collected before it can break down into smaller pieces such as those commonly found in open-ocean gyres, or large systems of rotating currents.

To prevent consumer waste such as plastic bottles and bags from reaching the coasts, municipalities have deployed trash capture technologies in some watersheds. These include storm drain inlet devices such as connector pipe screens, inline netting within pipes, hydrodynamic separators and trash

booms. Cleanup methods also depend on the type of waste. Removing large debris such as vessels, docks, large appliances or large nets “often requires heavy machinery and manpower, as well as a plan for disposing of it once it’s on land,” Wallace says. She also points to the recovery method for derelict fishing gear, which can be detected via side-scan sonar and retrieved using various types of hooks.

THE

THEORY - Use currents to have pollution come to you, rather than chase the garbage around the ocean—a costly and resource-intensive endeavor. But the research wasn’t thorough enough to convince the scientists the ocean array would succeed. They worried that inserting such an intrusive structure would have too many potential unintended consequences, including interfering with wildlife, to undertake the project. Good thought, they said, but try again.

So he did. Fast-forward three years, and Slat, 20, now has a 530-page feasibility study and $2.1 million in crowdsourced funding backing his Ocean Cleanup pilot project. The plan is to deploy a 6,561-foot prototype array designed to collect plastic off the coast of Japan in 2016. If all goes as planned, he’ll send off a production vessel measuring 62 miles long in 2020 that he says could remove 42 percent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch within ten years.

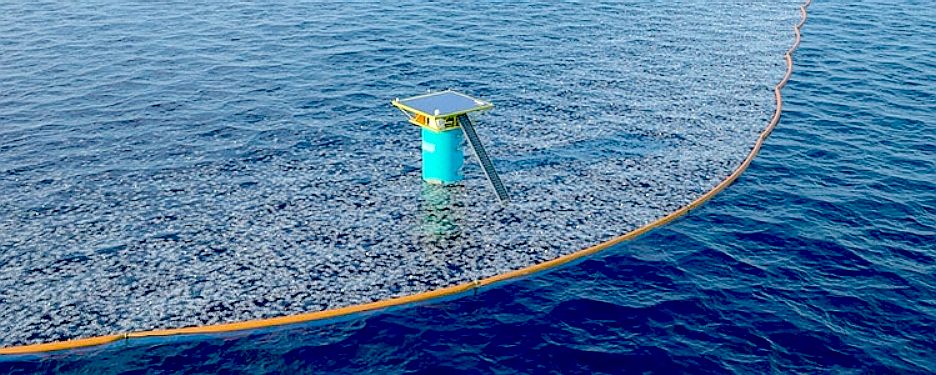

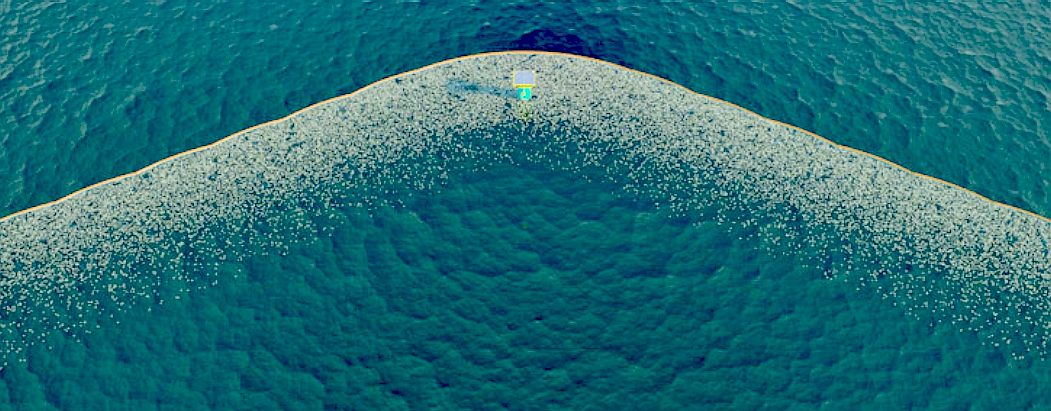

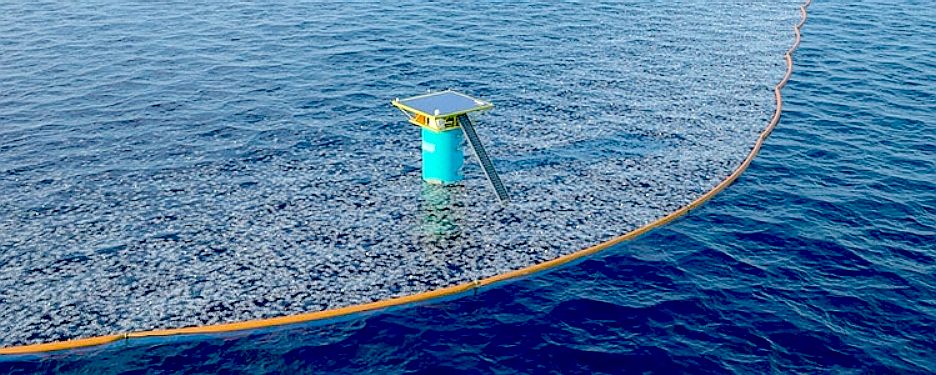

Until recently, approaches for large-scale plastic cleanup in the open ocean have been relegated to sketches on napkins. But a group known as the Ocean Cleanup will deploy in spring 2016 the first open water test of its barrier design in the North Sea 23 km from the Netherlands. The organization developed a scalable V-shaped array of barriers that passively catch plastic using ocean currents and winds. Beneath these barriers or “booms” a submerged non-permeable screen helps concentrate plastic suspended under the surface. Most of the currents will run beneath the screens. The project team says this feature will prevent so-called “bycatch” by carrying away all neutrally buoyant sea life.

The Ocean Cleanup’s first operational system is slated to deploy off the coast of Tsushima Island,

Japan, in the second half of 2016. By 2020, the company plans to send out a 100-km-long array into the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, home to the so-called Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The project’s ultimate objective is to harvest plastic from millions of square kilometers of open ocean.

Another recently announced project from a

UK company

proposes an autonomous vessel that collects floating plastic debris as it zooms through the seas. On-board wind turbines and solar panels will power the 140-foot-long trimaran known as the

SeaVax. The concept exists only as a one-twentieth scale model as its creators seek to finance a vessel for testing.

RIVERVAX™

- Is a potential solution for surface (and subsurface) river

and ocean pollution that is cost effective.

The value of such a versatile vessel might not be limited to the ability

to vacuum the Ganges

clean for example, but the blue water version, called SeaVax,

could target any area of the high seas that is rich enough in

plastic waste to make it worthwhile for the operators. This go

anywhere workboat is solar and wind

powered, another step forward for any nation that is doing their

level best to combat climate

change and acid oceans. The

vessel is designed to hold 150 tons of waste until it can

discharge at sea to a transfer tanker, or dock in port and

discharge directly to waiting treatment plants.

DEBRIS

RETRIEVAL LIMITATIONS

The Ocean Cleanup

has gained both fans and critics since it was announced in 2013. Jennifer Brandon says that the project solves some of the problems evident in other large-scale trash removal methods, but introduces other challenges.

“The best idea of their whole plan is anchoring in one spot and letting the current do a lot of the work for them,” says Brandon. She is a graduate student researcher specializing in marine micro debris at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of

California

San Diego. The system also surpasses “any-boat based cleanup method, which requires so much fuel and manpower going back and forth across the garbage patch,” she says.

One of the primary complications Brandon sees with open ocean cleanup is

biofouling. “Anything you leave in the ocean, even for a small amount of time, immediately gets colonized,” she says. Because this biofouling makes things heavier, the process could weigh down the array’s barriers to the point of breaking.

NAVIGATION

BLOCKER - Barriers measuring 6,500-feet to be deployed to help the oceans 'clean themselves' of millions of tons of plastic waste

So much plastic is dumped into the sea each year that it would fill five carrier bags for every foot of coastline on the planet, according to scientists, with many popular resorts blighted by rubbish.

But Dutch innovator Boyan Slat, 20, believes he's found a solution, with one of the most ambitious ocean cleanup missions that has ever been undertaken.

His aim is to rid the seas of millions of tons of plastic waste, but instead of conducting a sweep of all the ocean's junk, he plans to creatively let the ocean 'clean itself.'

Slat's non-profit organisation, The Ocean Cleanup Project, aims to halve the amount of plastic debris floating in the Pacific within a decade using giant, V-shaped floating barriers that will naturally capture waste using the current to their advantage.

A 6,561ft trial system is due to be installed in Japan this

year near to the island of Tsushimaand. It will become the longest floating structure in the world when

completed and the biggest navigation hazard to shipping all at

the same time.

Of even greater concern is whether the cleanup array can distinguish between plastic debris and organisms such as plankton and

fish

eggs. “Those things are so essential to the ecosystem of the entire ocean that it would do more harm than good to sort them out with the plastic,” Brandon says.

Some of the most damaging plastic waste is hard to detect with the

human

eye, let alone impossible to capture. These so-called microplastics come from three primary sources: microbeads are the miniscule plastic particles that add texture to soap, toothpaste and more; nurdles are the particles that act as raw material in producing plastic goods; and larger plastics degrading into smaller, irregular pieces also plague the ocean. Fish often mistake these microplastics for food.

To further outline potential challenges, marine debris researchers have produced a guidance document for prospective inventors of plastic-capture systems. The document recommends that designers account for strength and stability in extreme sea conditions, detectability by other vessels, legal issues and more.

BLUE

MARKER - Ships will need to be able to see where these

booms are located. Undeniably they present a potential danger

to marine traffic, unless good warning is given both visually

and digitally on maps - perhaps also with some kind of audible

warning system at night. You can just imagine the

entanglements that could arise, physical and legal.

Apart from navigation issues, the method is claimed to be environmentally-friendly as aquatic life and the currents are able to safely pass underneath the buffers, but the plastic will be gathered on the surface.

WHERE

DOES THE WASTE GO?

Because no one “owns” the ocean, no one technically owns the trash collected from it either. Often the burden falls to the country where the marine debris washes ashore, even though that country may have produced very little of it, says Scripps’ Brandon. Waste management also varies from country to country and the municipalities within it. Some areas still lack the waste infrastructure not only to manage the plastic debris but also to prevent it from reentering the waterways and oceans.

In the case of coastal cleanups, where collected trash ends up depends on what is in it and where it is removed, says Allison

Schutes, senior manager for the Ocean Conservancy’s Trash Free Seas program. She cites a “significant effort” among many places across the U.S. and elsewhere to keep as much of the trash out of landfills as possible. In areas with robust recycling programs, volunteers and municipality employees sort recyclables and non-recyclables. This helps ensure that much of the glass, metal and plastic collected are sent to local material recovery facilities, Schutes says.

Not all plastic trash can be recycled, however. “You need a high-quality plastic in order to recycle, and often that’s not the case because these plastics have been baking in the sun,” Brandon says.

When removing big pieces of debris such as abandoned vessels and commercial fishing gear, state and federal governments intervene as a matter of public health and safety.

NOAA

has identified best practices for cleaning, dismantling and disposing of derelict boats. These practices include vessel donation and turn-in programs, artificial reefing and recycling or scrapping.

Unique methods to reuse this debris are emerging. One example is the Fishing for Energy partnership between the NOAA Marine Debris Program, Covanta

Energy

and Schnitzer Steel administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The program features collection ports in marinas in nine states where old and damaged fishing gear may be discarded.

Steel

from the gear is recycled and the remaining line, rope

and nets are used for energy production.

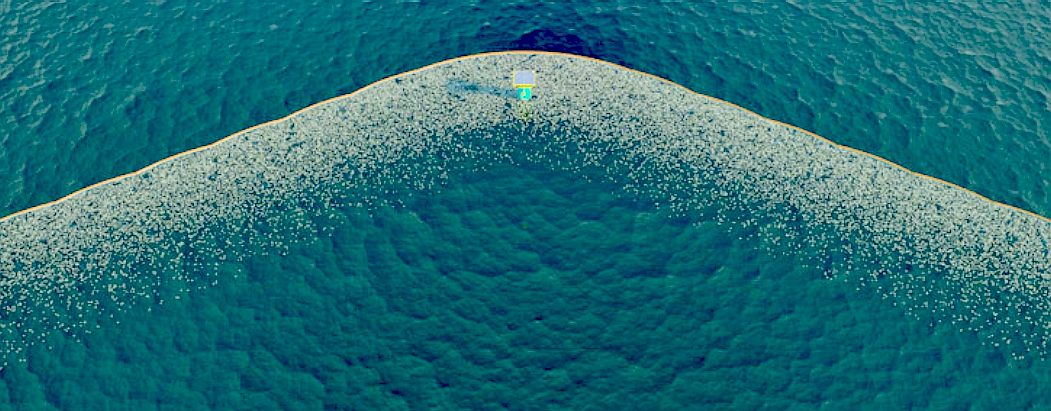

BOOM,

BOOM - Here’s how the tech works: The V-shaped ocean array will be made of 62 miles of floating barriers that drop, skirt-like, almost ten feet below the surface. (The Ocean Cleanup’s measurements have shown that the concentration of garbage decreases deeper than that.)

The array won’t move. Instead, it’ll be anchored to the seabed (12,795 feet below the surface) between

Hawaii and California in the North Pacific

Gyre - one of five major oceanic areas where currents converge

- collecting plastic and trapping the pollution at the surface while allowing marine life and plankton to continue flowing with the current under the barrier.

The team predicts that 80 percent of the plastic that hits the booms, up to 2,295 cubic feet per day, will be corralled, spun through a centrifuge, and transferred to a collection platform via a solar-powered machine. Every 45 days, boats will collect the plastic and transport it to shore. There, the plastic can be recycled or converted to oil. Estimates say the Ocean Cleanup will be 33 times cheaper and 7,900 times faster than conventional net-and-trawl proposals.

“Considering the fact that what we plan to do has never been done before,” Slat says, “it is likely we’ll come across operational challenges which will require tweaking the system. However, the basic

principles - the capturing and concentrating of plastic powered by natural

currents - have been extensively studied using both simulations and proof-of-concept tests.”

The rules for large-scale open ocean cleanup projects, by contrast, are a bit muddier because debris disposal of this magnitude is unprecedented. The Ocean Cleanup array funnels plastics toward its center, which allows a central platform to extract and store the plastic until a ship can transport it to land for recycling. When the system is fully deployed, project engineers expect a daily collection rate of 65 m³. This requires waste pickup every 45 days. The group expects a yearly cost of €1 million ($1.1 million), or €0.14 per kg plastic, to transport the garbage to land.

The project team has not yet indicated which country or countries will accept the trash. It is also unclear who’s responsible for sorting the plastics, a potentially labor-intensive task if organic materials like barnacles are attached to or entangled in the plastic. The company points to two possible outlets for the recovered refuse. Tests have shown that the waste plastic can be converted to oil through a process called

pyrolysis, a chemical reaction in which large molecules are broken down into smaller ones. Additionally, more than 30 companies have shown interest in buying the

plastic, which “we have shown is of surprisingly good quality and can be turned into high-quality projects,” says Lotte de

Groot, an Ocean Cleanup spokesperson.

NOAA’s Wallace says that new technologies for marine debris removal may play an important role in the future. Until then, she says, “it is important that we continue to work to prevent marine debris from entering the ocean in the first place.”

By

Winn Hardin

MARINE

LIFE - Clings to anything that floats, even toxic plastic

bottles retrieved from the North Pacific Ocean Gyre via the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

OUTSIDE

ONLINE JULY

21 2015

- NEVERTHELESS EXPERTS AREN'T CONVINCED

Their main concerns:

There’s no environmental impact statement.

The Ocean Cleanup isn’t holding itself to the same accountability standards as other large-scale engineering and mining operations in the ocean, partially because legalities are a gray area in international waters.

The device will miss the majority of plastic pollutants.

The booms are designed to trap floating pieces larger than two centimeters. But a majority of the ocean’s plastic, experts say, is in the form of degraded toxins much smaller than that. “Most of the plastic isn’t even at the surface waters that the array will be in,” says deep-sea ecologist and marine conservationist Andrew Thaler. “Now it becomes a question of what impact is this really going to have?”

OPEN

WATER HAZARD - Boyan Slat's company estimates that a 62-mile stationary cleanup array could remove 42 per cent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch over 10 years, representing a total of 70,320,000kg of plastic waste.

If the trial period proves successful, other Ocean Cleanup floating barriers, known as gyres, could be placed around the world to tackle the eight million tons of plastic in the seas.

However not everyone is convinced about whether or not the ocean-cleaning plans will be successful.

Deep Sea News outlined an analysis of the project and its feasibility, addressing issues like biofouling of the equipment, which it claimed had not been properly thought out.

Despite this, the plans are going ahead and combined with this, in

August 2015, 50 vessels were to be sent to scour the area between Hawaii and California to make the first hi-resolution map of plastic floating in the Pacific.

Slat has a team of 100 oceanographers, naval engineers, translators, and designers on hand, along with support from key political figures, like the mayor of Tsushima and of Los Angeles.

Slat began the Ocean Cleanup with a crowdfunding campaign in 2014 that raised $2million.

We would not want to be the Captain of a ship encountering

this obstacle at night. Are the towers to be lit up like

miniature lighthouses?

The potential effects on ocean life and ecosystems could be disastrous.

Floating structures in the ocean tend to act as fish aggregators, Thaler says, regardless of whether the species get trapped. This means the array, near which both fish and plastics will pool, could disrupt migration patterns, expose large populations of fish to more concentrated plastics, and have rippling effects on the marine life that ingests it.

The team hasn’t done enough research.

Going from concept to pilot technology of this scale in three years is very rushed, says Jenna Jambeck, associate professor of environmental engineering at the University of Georgia and co-author of the article “Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean” (Science, February 2015). “If it hasn’t been holistically and systematically integrated, we don’t know if it should happen,” Jambeck says. “We don’t even know enough about the ocean—that’s 70 percent of our planet—to know what the impact will be.”

Other experts agree: “It’s a project put together by engineers,” Thaler says. “They see a

problem - a lot of plastic in the ocean - and they figure out a solution for that. But they haven’t necessarily taken into account other related issues.”

Oceanographer Kim Martini and marine biologist Miriam Goldstein, who completed a detailed external review of the feasibility report for ocean news outlet Deep Sea News, feel that Slat and his team have not adequately addressed their concerns. They sum it up like this: “We continue to have serious reservations about the success of the project due to … the Ocean Cleanup’s substantive misinterpretation of oceanography, ecology, engineering, and marine debris distribution, all of which are necessary for this project to succeed.”

BOYAN

SLAT - The crazy Dutch inventor who's idea might prove to

be not so outlandish as some at first thought. Maybe we should

encourage those with the persistence to follow an idea like

this through. If it does not work, at least we can cross that

idea off our list of possible. If it needs tweaking, let the

experiments continue until it works as well as it might. The

only issue that we can see as an obstacle - and it is one heck

of an obstacle - is the booms themselves, as potential

navigation problem areas. No doubt Boyan has given this a

great deal of thought.

Slat wrote on The Ocean Cleanup's website:

'Taking care of the world's ocean garbage problem is one of the largest environmental challenges mankind faces today.

'Not only will this first cleanup array contribute to cleaner waters and coasts but it simultaneously is an essential step towards our goal of cleaning up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

'This deployment will enable us to study the system's efficiency and durability over time.'

Prevention is far more critical than extraction.

Many environmentalists say the resources and funding funneling into the Ocean Cleanup are deflecting attention away from the real need: making sure plastic doesn’t enter the ocean in the first place. Even if the equipment works flawlessly, will it matter in five years when the ocean is full of trash again? Thaler says it’s a societal state of mind: “We like technocratic

solutions - a piece of problem solving we can drop somewhere that doesn’t require us to change our behavior.”

Slat responded to many specific criticisms in this post, but perhaps the biggest takeaway from the Ocean Cleanup philosophy is this:

“It is not a question of either cleanup or prevention,”

Slat is quoted as saying. “It’s cleanup and prevention. If a cleanup started today, it would be a bit like mopping up the floor while the tap is still running. Prevention is absolutely essential. But until now, the mop hadn’t been invented yet. The plastic trash that’s out there won’t go away by itself.”

By: Julie Dugdale

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://ecowatch.com/2016/02/19/seavax-vacuum-ocean-plastic/

http://theterramarproject.org/thedailycatch/prototype-for-robotic-boat-suck-plastic-waste-unveiled-innovate-uk/

5gyres

blog posts 2016

gyres_in_india_contrasts_of_rich_and_poor_where_does_the_plastic_pollution_go

http://www.globalspec.com/

Outside

Online ocean doubt

DailyMail

UK news 20 year old inventors plan clean ocean five years

practise Japan year

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/search.html?s=&authornamef=Becky+Pemberton+For+Mailonline

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/search.html?s=&authornamef=Fiona+Macrae+for+the+Daily+Mail

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/travel_news/article-3112298/20-year-old-inventor-s-plan-clean-ocean-five-years-practise-Japan-year.html

http://www.outsideonline.com/1999216/ocean-doubt

https://www.youtube.com/user/TheOceanCleanup

https://scripps.ucsd.edu/

http://www.oceanconservancy.org/

http://www.theoceancleanup.com/

http://insights.globalspec.com/article/2132/cleanup-systems-aim-to-stem-the-tide-of-ocean-plastic-pollution

http://www.globalspec.com/

http://www.5gyres.org/blog/posts/2014/04/17/5_gyres_in_india_contrasts_of_rich_and_poor_where_does_the_plastic_pollution_go

http://www.bluebird-electric.net/oceanography/Ocean_Plastic_International_Rescue/SeaVax_Ocean_Clean_Up_Robot_Drone_Ship_Sea_Vacuum.htm

http://theterramarproject.org/thedailycatch/prototype-for-robotic-boat-suck-plastic-waste-unveiled-innovate-uk/

https://ecowatch.com/2016/02/19/seavax-vacuum-ocean-plastic/

http://www.energymatters.com.au/renewable-news/solar-wind-seavax-em5350/

http://www.csiro.au/en/News/News-releases/2015/Marine-debris

http://www.express.co.uk/search/Maisha+Frost%252C+Exclusive?s=Maisha+Frost%2C+Exclusive&b=1

http://www.express.co.uk/finance/city/638166/New-cleaner-SeaVax-has-solution-to-ocean-plastic-waste

|